Is Laura Mulvey’s Feminist Film Theory Still Relevant?

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” gap=”35″][vc_column width=”2/12″ css=”.vc_custom_1561015863493{padding-right: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;}”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”6/12″][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1565607957315{margin-bottom: 100px !important;}”]Laura Mulvey is a British film theorist who moved the realm of theory and film perception through her writings by combining film theory, psychoanalysis, and feminism. She is a pioneer in breaking down the role of men and women in Hollywood. Her essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema was first published in 1975 in the journal Screen where she extensively applies Freud and Lacan.Films and TV shows are dropped every day in massive numbers. Just like in any other industry, it goes without saying that progress shares a symbiotic relationship with cinema and the visual culture and that the visual arts of an era depict and mimic the ideologies which are heavily laced with biases and linear viewpoints, but as all art is political, the aforementioned qualities cannot be dissociated. Period. One of the most striking features of cinema (and mind you, not just Bollywood) is the way in which women are viewed and represented. This was first theorized and broken down by Laura Mulvey in her essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ (1975) wherein she looks at the position of women through a psychoanalytical lens. The film form is inherently structured by the patriarchal unconscious of society is the central focus of her essay. Mulvey suggests that a woman is always the object to the subject of the man. This binary opposition is established by the structuring of the narrative, and the use of the camera (movements and angles) help in fixating and strengthening this position. In short, the camera’s gaze becomes the spectator’s gaze when the fourth wall is obscured, and hence this gaze intrinsically becomes the masculine ‘male gaze’. Although Mulvey’s theory is based on Hollywood, gender treatment is observed to be the same even in Bollywood.

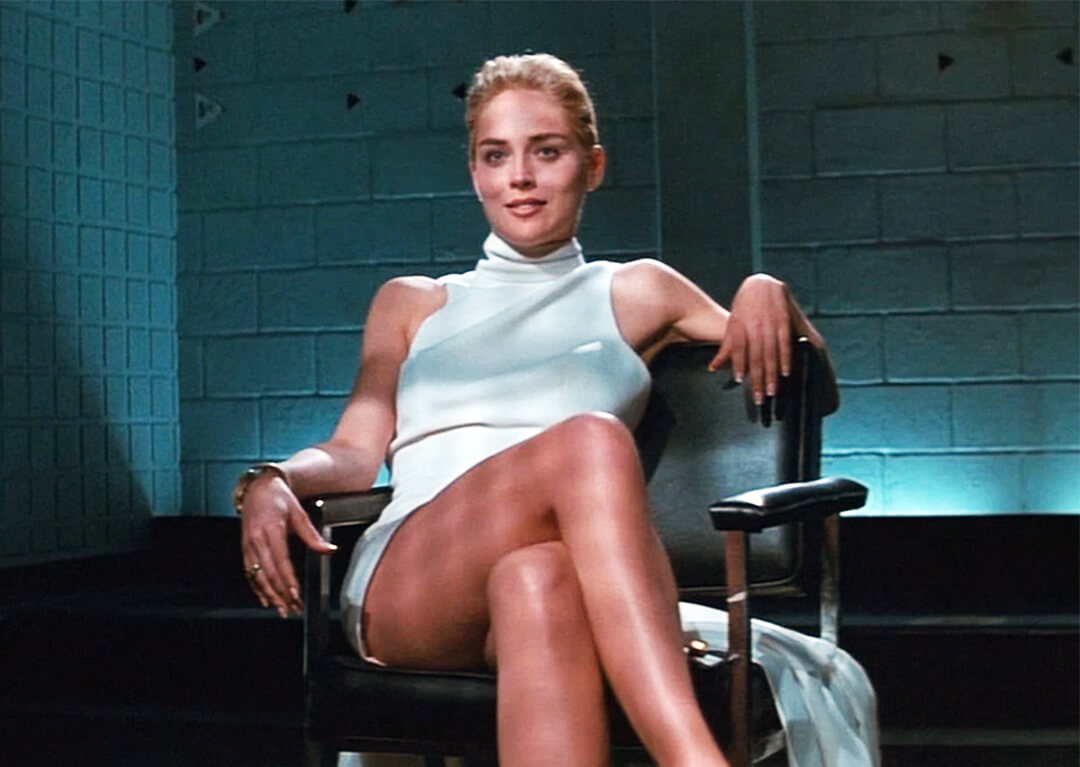

The spectator always sees through the eyes of a heterosexual man and the pleasure derived is scopophilic in nature. Scopophilia in simpler terms is the pleasure derived by looking at something, in this case, the pleasure derived looking at a woman who is often naked or scantily clad (what did you think Sheila’s ‘jawaani’ was?) A man is always considered as the active member (I mean, take any mainstream Bollywood film) whereas the female is undoubtedly the passive counterpart. The heterosexual male as represented in Hollywood through various cinematic apparatuses is the owner of the sight and the woman is the image who is the object of a man’s sexual pleasure. Few unambiguous examples of the male gaze include shots which pan and fixate on a woman’s body, medium close-up, over the shoulder shots of women and scenes which show a man actively looking at a passive female. Mulvey also points out that the woman is always at the two ends of the spectrum; someone who is to be saved by the ‘hero’ (yes, Basanti, looking at you) and/or someone who needs no rescuing and is the ultimate threat to the man; the Femme Fatales who weaken a man’s ‘manliness’, but are again sexualized and/or unattainable and there are no better Femme Fatales than Catherine Tramell of Basic Instinct, Amy Dunne the Gone Girl and Khalu from Ishqiya.

Catherine Tramell from Basic Instinct (1992)

Catherine Tramell from Basic Instinct (1992)

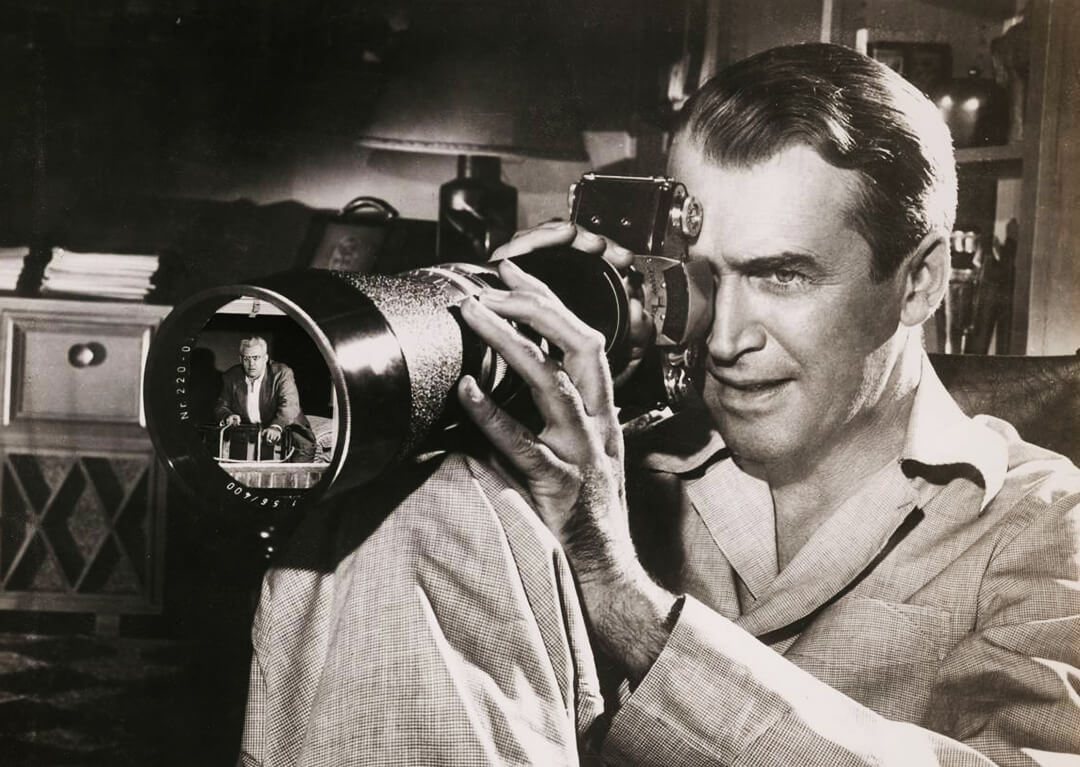

Hitchcock’s Rear Window is a brilliant example which helps us understand the “gaze”. Jefferies, a photographer in Rear Window, is put in such a situation which makes him a voyeur. Due to a broken leg, Jeffries is confined to the four walls of his bedroom, his only pastime being, looking at people through his bedroom window. This film reveals to us one of the most important needs of a man; to peep through the keyhole at every given opportunity which is often supported by ‘curiosity’. The film is highly male-centric and a direct representation of how the visual culture in Hollywood is male-centered. The second example on the other side of the spectrum is Uma Thurman’s character ‘The Bride’ from Kill Bill, who in the very first few minutes of the film commits two murders, steals a car and escapes from the hospital where she was in a coma for four years. This strong-willed character posits as a threat to the man. She hardly wears make-up, rarely smiles and is more ‘manlike’ than most female characters. These two characters in the narratives in the respective films, drive them in two different directions which ultimately provide the position of a woman in commercial cinema. As for Bollywood until recently, most films are through the male gaze to satisfy the very same pleasure-driven voyeuristic attitude. Going back to Sholay, both the women characters; Radha (Jaya), a meek widow and Basanti (Hema Malini) an extroverted cart driver is portrayed to be on the opposite ends of this spectrum, but although independent, Basanti is saved by Veeru (Dharmendra) from the hands of Gabbar the iconic villain played by Amjad Khan. The recently released Kabir Singh is another such movie which disturbingly aids and strengthens the male gaze that runs rampant in the industry.

L.B ‘Jeff’ Jefferies from Rear Window (1954)

L.B ‘Jeff’ Jefferies from Rear Window (1954)

Mainstream cinema aside, we had Satyajit Ray bring female gaze, or rather a refreshing perspective with Charulata which is one of the most monumental films of Indian cinema. In recent times there has been a slight shift in the way in which women are portrayed or even “looked at” Vidya (Vidya Balan) in Kahaani, the relentless and thrifty protagonist who does not resemble a generic Bollywood heroine or Meera (Anushka Sharma) in NH10 and Sehmat (Alia Bhatt) in Raazi are the ones who have made that shift seem natural. All the three characters portray a varied mix of revenge and survival which makes it believable, interesting and realistic. Another notable character is Shashi from English Vinglish written and directed by Gauri Shinde. Sahashi’s character is a docile homemaker cum businesswoman who is taunted by her husband and daughter for not speaking English and hence finds it empowering to learn English. Her character is beautifully created and has no frills or any glamour element attached to it which keeps it away from the generic male gaze. As for the literal ‘gaze’ viz. the camera angles and movements are again quite neutral and well-rounded rather than linear. Their characters are not viewed from the dominant male ideology, but rather an impartial one.

Shashi Godbole from English Vinglish (2012)

Shashi Godbole from English Vinglish (2012)

Mainstream cinema is making a definite shift from dominant ideologies, but as long as women are looked at like objects, the movies made by men will always be portrayed through the ‘male gaze’. This pattern is, unfortunately, a vicious circle where the cause and effect of what is portrayed on the screen seem to have a blurred line. To put this into perspective – we don’t know if a man treating a woman as if she needs saving is largely a product of what we watch, hear and see and vice versa as most of what we see and experience in the realm of pop culture is what gets internalized. Mulvey arrived at this conclusion mainly because the cinematographers, writers, directors, etc. who were mostly men made a film based upon their outlook and ideologies. This is nevertheless taking a turn as we more women filmmakers in this vast field of visual culture.

Works cited: Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. Eds. Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2000. 585-95. Print.

About The Author

Priya is a 20 something yoga instructor and avid beverage enthusiast who is fueled on coffee and loves taking pictures on her 35mm and secretly believes that she is as badass as The Punisher. She is also a tree hugger, a lover of noisy music and is extremely awkward when it comes to getting her pictures clicked.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/12″ css=”.vc_custom_1587562455126{border-left-width: 5px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #f5f5f5 !important;border-left-color: #1e73be !important;}”][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1587562425498{margin-right: 20px !important;margin-left: 20px !important;border-right-width: 20px !important;border-left-width: 20px !important;}”]

Priya is a 20 something yoga instructor and avid beverage enthusiast who is fueled on coffee and loves taking pictures on her 35mm and secretly believes that she is as badass as The Punisher. She is also a tree hugger, a lover of noisy music and is extremely awkward when it comes to getting her pictures clicked.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/12″ css=”.vc_custom_1587562455126{border-left-width: 5px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #f5f5f5 !important;border-left-color: #1e73be !important;}”][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1587562425498{margin-right: 20px !important;margin-left: 20px !important;border-right-width: 20px !important;border-left-width: 20px !important;}”]

Continue Reading

[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”5″ element_width=”12″ gap=”35″ item=”10912″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1587562428349-4195e0d2-675c-4″ el_class=”grp”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” gap=”10″ equal_height=”yes” content_placement=”top” css=”.vc_custom_1559458142539{background-color: #1b0341 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]50 HOUR FILMMAKING CHALLENGE

Know More

Rules

FAQs

Jury

Awards

Previous Winners[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

CHALLENGES

Short Scriptwriting Challenge

Storytelling Challenge

Poster Design Challenge[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

FESTIVAL

Schedule

On The Stage

Venue and Travel

BUY PASSES[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]About IFP

Previous Editions

Branded Content

Labs

Campus Connect

HELPLINE – 9727299070

EMAIL – [email protected][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]